Dear Friends,

It is with solemn hope and urgency that we transmit to you the enclosed report: Shadow Citizens: Confronting Federal Discrimination in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The U.S. Virgin Islands embodies many of our country’s most troubling racial disparities, particularly in healthcare. At the same time, the Territory remains largely invisible in our emerging national conversations surrounding racial justice and democracy. The enclosed report details critical areas of federal law and policy that discriminate against the U.S. Virgin Islands and relegate the Territory’s low-income and disabled population to an unconscionable second-class status.

This discrimination must be remedied.

Amid continued efforts to rebuild the U.S. Virgin Islands in the wake of Hurricanes Irma and Maria (2017) and COVID-19, federal policy must account for longstanding structural problems that have harmed the Territory since long before the pandemic or 2017 storms. From Medicaid to Supplemental Security Income to federal data collection, today’s federal programs pose a systemic obstacle to rebuilding the Virgin Islands on a more lasting and equitable footing. The recommendations contained within the report provide a roadmap toward reducing some of our nation’s most glaring inequities and extending support to areas where it is most needed.

The first of April will mark the U.S. Virgin Islands’ 104th year as a United States territory. Despite unceasing outward promises of equality before the law, the United States has allowed alarming disparities to grow even more glaring and blatant over time. Residents of U.S. territories have been written out of major federal infrastructure and benefits programs responsible for lifting millions of other Americans out of extreme poverty, despite collectively paying billions of dollars into the U.S. Treasury and shedding blood in every American conflict over the past century. The Territory lags behind the rest of the United States in nearly every key economic and social metric: 34% behind the poorest U.S. State in per capita income while cost-of-living has soared to 40-50% above the national average.

The United States is engaged in a sobering period of division. Today’s lawmakers may not be able to furnish answers to the territories’ most fundamental questions of political status or self-determination, but they can begin to put an end to this egregious inequity.

Respectfully,

Amelia Headley LaMont

Executive Director, Disability Rights Center of the Virgin Islands

Report Summary

Report Summary

The U.S. Virgin Islands faces unique structural obstacles as a United States territory. Not only are U.S. citizens living in the Virgin Islands denied voting representation in the national government, they are denied full access too many of our nation’s most important federal programs. The harmful effects of this discrimination are felt most acutely by Virgin Islanders with disabilities, who are denied access to basic federal safety-net programs that are essential to most disabled and low-income Americans’ well-being. With a population that is three-quarters Black, the U.S. Virgin Islands embodies today’s growing national conversation around racial disparities in health care, which have grown extreme on account of discriminatory treatment under federal Medicaid laws. As Virgin Islanders’ access to care suffers the mounting burdens of both Hurricanes Irma and Maria and of COVID-19, local and national advocates must urgently speak up for one of the nation’s most disadvantaged and unheard communities. Amid the continued policy making focus on hurricane recovery and COVID-19 response efforts, local and national leaders must not ignore the longstanding structural problems and discriminatory federal benefits laws that have plagued the U.S. Virgin Islands since long before the pandemic or 2017 storms.

Key Recommendations

• Remedy decades of unequal treatment under federal Medicaid laws. Remove discriminatory funding caps and unequal reimbursement formulas. Reduce U.S. territories’ year-to-year funding uncertainties to enable longer-term healthcare investments and initiatives.

• Remedy decades of exclusion from Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Ensure full eligibility for disabled, blind, and elderly Virgin Islanders who would otherwise qualify if they resided in a State, Washington D.C. or the Northern Mariana Islands.

• Reduce disparities in health insurance availability and uninsured rates enabled by U.S. territories’ unequal treatment under the Affordable Care Act.

• Eliminate inconsistent data collection negatively impacting U.S. territories, including the U.S. Virgin Islands’ exclusion from American Community Surveys (ACS). Ensure federal agencies and Congress collect and report Virgin Islands demographic, health, economic, and tax data using the same methods employed for the fifty states and Washington D.C.

• Increase U.S. Virgin Islands representation in Washington D.C., particularly before the U.S. Senate and its committees.

• Raise public awareness of discrimination against U.S. territories in federal programs like SSI and Medicaid. Explore remedies that may be available through territorial or federal courts.

Introduction

Emerging national conversations about systemic racism have renewed attention to one of the United States’ most overlooked inequalities: the diminished rights of citizens living in U.S. territories like the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

There is no community in the United States that experiences more dimensions of modern structural inequality than the disability community of the U.S. Virgin Islands. A Territory inescapably marked by the European-American plantation economy and the triangular slave trade, the U.S. Virgin Islands has lagged behind the rest of the United States in nearly every metric of economic growth and stability. Even before 2017 Hurricanes Irma and Maria, the Virgin Islands’ per capita income lagged 34% behind the poorest U.S. State and 51% behind the national average, while the present cost of living has ballooned to exceed the national average by 40-50%.1 According to the 2010 U.S. Census, approximately 23% of Virgin Islanders lived below the federal poverty level—nearly double the average of the 50 states.2 Three-quarters of the population is Black.

As in other U.S. territories, U.S. citizens residing in the Virgin Islands are disenfranchised across all three branches of the federal government. Despite having U.S. citizenship by birth, the U.S. Virgin Islands gets zero electoral votes for President, zero U.S. Senators, zero voting representation on the floor of the House of Representatives, and no Article III protections for its federal judges. The Virgin Islands’ lack of a meaningful, equal voice in Washington D.C. means that federal law or policy making that excludes U.S. territories is more likely to go unnoticed or unchallenged until it is too late.

The real-world impact of the Territory’s exclusion from key federal programs—and from the federal government itself—is felt hardest by disabled Virgin Islanders. Virgin Islanders with disabilities have been completely shut out from benefits like Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which provides low-income disabled persons up to $800 per month in income assistance throughout the 50 states, Washington D.C., and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Similarly, the Virgin Islands’ healthcare landscape has been devastated by unpredictable and discriminatory treatment under federal Medicaid laws. Decades of discriminatory funding caps and diminished reimbursement formulas under Medicaid have done as much damage to the Virgin Islands’ healthcare ecosystem as the 2017 hurricanes, which physically destroyed most of the Territory’s already distressed infrastructure. These are just two of many examples of how federal disenfranchisement and exclusion from federal programs have left disabled Virgin Islanders both without a voice and without the support they need for basic life activities.

This report highlights just a few of the issues in federal law and policy that contribute to the systemic disenfranchisement and short-changing of the Virgin Islands’ disability community compared to similarly situated communities in the mainland United States. Its purpose is to simplify some of the complex issues in federal law that have enabled this harmful discrimination against the Virgin Islands and to assess its impact on one of the nation’s most unrepresented communities. It is also intended to shed light on deeper policy issues and structural harms that risk being ignored as policymaking centers increasingly on hurricane and pandemic related impacts.

In just the past several months, advocates in other territories have successfully challenged discriminatory exclusions from federal benefits like SSI or nutrition assistance, setting the stage for an upcoming battle before the U.S. Supreme Court.3 In Puerto Rico, a disabled citizen recently won a lawsuit declaring the federal government’s discriminatory treatment of Puerto Rico residents under the SSI program unconstitutional. In Guam, another court reached the same result after a woman who moved to Guam was cut off from benefits that her twin sister (who has an identical disability) receives in Pennsylvania. Regardless of what relief can be pursued in court, the Virgin Islands cannot afford to take a wait-and-see approach to remedying disenfranchisement and discrimination at the federal level.

About DRCVI

The Disability Rights Center of the Virgin Islands’ (DRCVI) core mission is to provide zealous, creative, and innovative advocacy on issues of importance to the Virgin Islands’ disability community. We focus these efforts towards affirmatively addressing the needs of traditionally underrepresented and underserved communities through partnerships within those communities. With offices on both St. Thomas and St. Croix, DRCVI integrates a variety of advocacy approaches, including self-advocacy, legal, non-legal, media, public policy and investigatory work.

Background

Throughout its history as a United States territory, the Virgin Islands has been written out of major federal infrastructure and benefits programs.

The first U.S. President to visit the Virgin Islands, Herbert Hoover, openly called the Territory a “poorhouse,”4 suggesting that the islands offered little value to United States and declaring it “unfortunate that we ever acquired these islands.” 5 However, President Hoover still acknowledged, even if reluctantly, that because the United States “assumed the responsibility for the [Virgin Islands], we must do our best to assist the inhabitants.” 6

The first U.S. President to visit the Virgin Islands, Herbert Hoover, openly called the Territory a “poorhouse,”4 suggesting that the islands offered little value to United States and declaring it “unfortunate that we ever acquired these islands.” 5 However, President Hoover still acknowledged, even if reluctantly, that because the United States “assumed the responsibility for the [Virgin Islands], we must do our best to assist the inhabitants.” 6

But in the years since President Hoover’s visit, the United States has not included the Virgin Islands in essential benefits and infrastructure programs responsible for lifting millions of other Americans out of extreme poverty. Instead, the standard-of-living gap between U.S. citizens in the Virgin Islands and those living on the mainland is widening in key respects. In the words of one legal scholar, “the continued denial of these [Virgin Islands] as truly American demonstrates that how we define ‘American’ contains an economic calculation.” 7

Historically, the most common justification offered for excluding the Virgin Islands from full access to crucial safety-net programs like Medicaid or Supplemental Security Income has been the tax status of U.S. territories. In courts and in Congress, those who defend these exclusions have argued that territories like the Virgin Islands can be excluded from full protection because their residents do not pay taxes into the federal treasury. However, as a number of federal courts have recently observed, this argument no longer holds true.

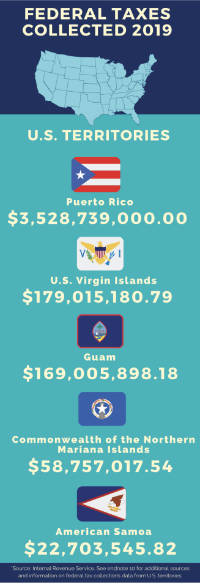

Today, U.S. territories collectively pay billions of federal tax dollars into the U.S. Treasury every year, more than the residents of Vermont, Alaska, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana in recent tax years.8 Even though most residents’ personal income tax remains in the Territory, the Virgin Islands and other territories are subject to numerous types of federal taxation: FICA taxes, SECA taxes, unemployment insurance taxes, estate taxes, and gift taxes, to name a few.9 Newly obtained tax collections data from the Internal Revenue Service show that for 2018 and 2019 alone, the federal government collected nearly $300 million from Virgin Islanders across nine different categories of federal tax.10 As a federal appellate court recently explained, “the argument that [territorial] residents do not contribute to the federal treasury is no longer available.”11

More significantly, the most critical federal programs that currently discriminate against residents of the Virgin Islands are designed to support the nation’s lowest-income populations—populations that generally do not pay federal income taxes no matter where they live in the United States. A large share of these benefits goes to persons who may never enter the U.S. workforce at all. Several federal courts have recently suggested that it is both irrational and unconstitutional for Congress to extend a lifeline to low-income disabled populations everywhere in the United States except for territories like the Virgin Islands where the need is arguably most pressing.12

The U.S. Virgin Islands’ federal funding uncertainties are accelerating. Longstanding structural problems have combined with the destructive impacts of Hurricanes Irma and Maria on physical infrastructure and of COVID-19 on the Territory’s tourism-centered economy. In February 2020, even before COVID-19 was declared a national emergency in the United States, the Government Accountability Office reported that the Virgin Islands’ public revenues had been cut essentially in half since 2017, projecting that a full economic recovery could take years.13 Just three months later, economic losses from COVID-19 had made the Territory’s financial situation noticeably worse, forcing the Virgin Islands Government to slash most agency budgets by another 15% on average.14 More recent projections suggest that the Territory’s largest unfunded financial commitment, the Virgin Islands’ Government Employees’ Retirement System, is now headed towards insolvency by 2023 or sooner.15 And in March 2020, the Virgin Islands’ public healthcare facilities surpassed $50 million in debt despite funding increases associated with the 2017 Hurricanes.16

Temporary funding increases, short-term disaster relief appropriations, and emergency stopgap measures—although sorely needed—cannot resolve the underlying problems that continue to threaten the basic well-being of low-income and disabled Virgin Islanders. Policy proposals that focus exclusively on one-year or two-year solutions will necessarily fail to account for the deeper forms of discrimination and exclusion that have destabilized the Territory since well before Hurricanes Irma and Maria and COVID-19. Instead of taking a “wait-and-see” approach as federal benefits discrimination continues to be litigated in federal courts, lawmakers should take initiative to address the structural disadvantages embodied in federal laws and benefits programs that consistently leave disabled and disenfranchised Virgin Islanders behind.

Unequal Treatment Under Medicaid Laws

Medicaid Overview

Medicaid is the primary means by which low-income Americans obtain health coverage. More than 1 in 5 Americans are currently covered by Medicaid—including nearly half of all children with special healthcare needs. Some 10.7 million of those Medicaid recipients are low-income individuals with a disability.17 As is the case in low-income communities of color across the United States, the physical health and well-being of the U.S. Virgin Islands rests largely upon the shoulders of federal funding for Medicaid.

Medicaid is the primary means by which low-income Americans obtain health coverage. More than 1 in 5 Americans are currently covered by Medicaid—including nearly half of all children with special healthcare needs. Some 10.7 million of those Medicaid recipients are low-income individuals with a disability.17 As is the case in low-income communities of color across the United States, the physical health and well-being of the U.S. Virgin Islands rests largely upon the shoulders of federal funding for Medicaid.

At its core, Medicaid is a cost-sharing program in which the federal government reimburses state and territorial governments for providing no-cost health insurance to their lowest-income residents. Its funding structure is designed to provide greater federal assistance to communities with the greatest economic need using a formula set by law—the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). Each state’s federal reimbursement percentage, or FMAP, is calculated based on the state’s per capita income. In other words, the lower a state’s per capita income is, the higher its federal reimbursement percentage will be.

Wealthier states like Maryland, California, and New York have the lowest possible base FMAP of 50%, meaning that absent special adjustments, the federal government covers only 50% of costs associated with Medicaid coverage. In poorer states like West Virginia or Mississippi, however, the federal government will cover 75% or more of costs under the current FMAP formula. The highest base reimbursement percentage for 2021 is 77.76% (Mississippi), meaning that for every $100 spent on Medicaid services, the State of Mississippi pays $22.24 while the federal government pays $77.76.18

Discriminatory Federal Medicaid Rules for the U.S. Virgin Islands

For the last several decades, Congress has maintained discriminatory rules affecting how the normal FMAP cost-sharing formula is applied in U.S. territories, effectively slashing federal support for low-income and disabled Virgin Islanders by tens of millions of dollars per year. By holding the Virgin Islands in a separate and lesser eligibility status, Congress has turned Medicaid—a program designed to give increased federal support to communities with the lowest per capita incomes—on its head.

Medicaid’s disparate treatment of low-income and disabled Virgin Islanders is best illustrated by comparing the Territory’s funding rates to states with comparable per capita incomes. In 2016, Mississippi had the lowest per capita income of any state ($35,613), which allowed its Medicaid program to receive the highest federal reimbursement percentage (74.17%).19 In comparison, the U.S. Virgin Islands’ per capita income for 2016 was just $23,333, about 35% lower than any state’s.20 Under the standard Medicaid formula, the U.S. Virgin Islands’ federal reimbursement rate should have equaled or exceeded Mississippi’s. Instead, Congress adopted a separate and arbitrary rule setting the Virgin Islands’ FMAP at just 55%, a rate that normally corresponds to some of the wealthiest states in the Union.21

In addition to removing the U.S. Virgin Islands from the normal cost-sharing formula, discriminatory federal Medicaid laws have erected an additional barrier that disadvantages low-income, disabled, and disenfranchised communities in the Virgin Islands: overall funding caps. In the 50 states and Washington D.C., there is no fixed limit on the amount of federal reimbursement money that a Medicaid agency can receive under the FMAP cost-sharing formula. In the Virgin Islands, however, Congress has specifically enacted a fixed ceiling on the total funding that the Virgin Islands may receive in a given year. These arbitrary federal spending caps mean that the Territory can receive even less than what the already-diminished FMAP reimbursement rate would suggest

Once the overall cap is reached, the Virgin Islands “must assume the full cost of Medicaid services or, in some instances, may suspend services or cease payments to providers until the next fiscal year.”22 In other words, the statutory reimbursement percentage only applies up to a certain dollar amount—once that amount is reached, 100% of costs fall on the Territory.

This is not a hypothetical scenario. The Congressional Research Service recently concluded that “[p]rior to the [Affordable Care Act], all five territories typically exhausted their federal Medicaid annual federal [sic]capped funding before the end of the fiscal year.”23 In 2000, for example, although the federal government’s stated cost-sharing ratio for Virgin Islands Medicaid was 50%-50% on paper, the funding cap kicked in and produced a very different result:

After applying the cap, the local government had to contribute nearly $8.1 million from its own funds, and in-kind services. The true ratio of contribution in 2000 was, therefore, 37% Federal and 63% local. 24

In contrast, the true ratio of Medicaid contribution in FY2000 for the state of Vermont, whose per capita income is thousands of dollars higher than that of the U.S. Virgin Islands, was the exact opposite: 63% federal and 37% local.25

More recently, these shortfalls have been averted with short-term legislative fixes that lift or avoid the cap on a temporary basis. For instance, provisions of the federal Affordable Care Act appropriated new Medicaid funding for the Virgin Islands that was exempt from the normal overall cap through 2019, temporarily avoiding the statutory ceiling.26 Regardless of whether and how Congress intervenes to mitigate budget emergencies, this system of arbitrary federal Medicaid caps followed by temporary work-arounds puts the Virgin Islands in a perpetual state of budgetary uncertainty, limiting its ability to plan for and invest in the healthcare system’s future.

As with the other federal programs described in this report, the separate and discriminatory rules governing the territories’ unequal treatment under Medicaid are legally complex and not easily summarized. The rules’ ever-changing complexity contributes to a lack of public awareness of how these federal issues affect local outcomes, and more specifically, how the current state of Virgin Islands healthcare directly reflects these discriminatory laws.

Affordable Care Act Related Federal Healthcare Discrimination

To understand the full impact of the Virgin Islands’ separate status under Medicaid, policymakers must also take notice of other features of federal law and policy that disadvantage the Virgin Islands compared to the 50 states or Washington D.C. The first surrounds the Virgin Islands’ high rate of uninsured individuals and relative lack of private health coverage options, both of which were exacerbated by the Territory’s separate treatment under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).27 The health insurance situation in the U.S. Virgin Islands is especially dire even compared to the other territories. As of 2014, even before Hurricanes Irma and Maria, 30% of Virgin Islanders lacked health insurance coverage—four times the uninsured rate in Puerto Rico (7%).28 In 2016, 61% of Virgin Islands children between ages 10 and 19 were uninsured.29

These extraordinary numbers of uninsured citizens parallel many of the core healthcare problems that led Congress to pass the Affordable Care Act. Still, the Virgin Islands was left out of many of the ACA’s key reforms, leaving an increasing number of people in limbo and increasing the stakes of Congress’s decades-long underfunding of the Territory’s Medicaid program.

At its core, the ACA was designed to expand healthcare coverage by a combination of (1) market reforms (for example, ensuring the availability of individual health plans through state exchanges and prohibiting coverage exclusions based on pre-existing conditions), (2) individual and employer mandates, and (3) subsidies for lower-income Americans who may not qualify for Medicaid but struggle to afford private health coverage. These three features of the ACA have been analogized to the legs of a stool—all three features were designed to work together to increase access to healthcare coverage under this statutory scheme.

As a result of several confusing provisions establishing separate rules for U.S. territories (including conflicting statutory definitions of the word “State,” which included the U.S. Virgin Islands for some portions of the law but not for others),30 Congress ultimately enacted a watered-down version of the ACA for the U.S. Virgin Islands. Even before the law took full effect, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) anticipated several key problems that would result from the ACA’s separate rules for U.S. territories. NAIC noted that “two legs of this stool will be weakened, as the individual and employer mandates will not apply, and the funds available for subsidies will not be sufficient to cover all eligible individuals” in U.S. territories.31 NAIC’s report further noted that if the Virgin Islands were to attempt to establish its own health care exchange under the ACA, it would receive only “a limited allotment of subsidy funding that only covers a fraction of needed funds,” such that “the threat of adverse selection driving up premiums” would be “significantly higher in the territories than it is in the states.”32 Ultimately, NAIC concluded that the ACA’s disparate treatment of U.S. territories would risk significant market destabilization in the U.S. Virgin Islands without Congressional or administrative intervention to increase subsidies or otherwise put the territories on more equal footing with states.

Although the full impact of the Virgin Islands’ separate treatment under the ACA has yet to be fully measured, the gap in outcomes is already apparent. During its first five years in operation, the ACA dramatically reduced the nation’s percentage of uninsured adults to historic lows, with the most significant gains occurring among Americans of color at or near the federal poverty level.33 Meanwhile, in the Virgin Islands, uninsured rates continued to grow, ballooning to nearly triple the national adult average by 2016-17.34

As of the time of this report, none of the territories has established or otherwise secured access to an individual healthcare exchange under the Affordable Care Act, in contrast to all fifty states and Washington D.C., all of which had either established their own exchanges or had an exchange created for them by the federal government as of 2013. Rather than include U.S. territories in the full package of reforms, the ACA instead set aside a limited pool of money that the Virgin Islands and other territories could elect to use for one of two purposes: (1) to establish a healthcare exchange or (2) to expand Medicaid coverage for the next several years. As a result of decades of systemic underfunding of Medicaid in U.S. territories described in the previous section of this report, the territories had overwhelming incentives to use this one-time ACA grant to alleviate years of financial strain on Medicaid programs.

Predictably, all five territories chose the second option: Medicaid expansion. Although framed as giving territorial governments a choice with respect to the ACA, the first option—combatting private health insurance unavailability by establishing a healthcare exchange—was never clearly viable. For example, the one-time grant made available to U.S. territories through the ACA would have been insufficient to cover even the first year of subsidies needed for new individual enrollments on a private exchange.35 According to one actuarial report, the federal government’s one-time $24.9 million subsidy to cover reform from 2014 to 2019 “would leave the territory with a $9.6 million gap the first year, and $147.6 million in underfunding over the next five years.”36 Other sources reported several additional disadvantages facing U.S. territories in realizing any potential benefits of the ACA with respect to the private insurance market. Some of these disadvantages were features of the law itself, while others arose through implementation. For instance, the St. Thomas Source reported that territories like the Virgin Islands “were only authorized to apply for exchange planning grants in 2011, a year after most states, leaving less time to complete studies relevant to determining their best path” prior to implementation deadlines.37

Real-World Impacts: Medicaid and Health Policy Discrimination

Financial Impacts

There are many different ways to measure the real-world impact of the Virgin Islands’ separate status under federal Medicaid laws. The simplest one is in dollars. By way of example, the Virgin Islands spent $16.1 million in local funds on Medicaid in FY2011. Based on a federal reimbursement percentage of 50%—the rate set by Congress for the Virgin Islands that year—the Territory’s anticipated federal funding would theoretically come out to an identical $16.1 million (absent special caps or adjustments).38 The Medicaid federal funding contribution for the Virgin Islands would have tripled had it received equal treatment under the standard FMAP formula.

Even if it had been treated the same as the lowest-income state (Mississippi, whose per capita income was significantly higher than that of the U.S. Virgin Islands in 2011), the projected federal reimbursement would have been $47.61 million. Put differently, for FY2011 alone, Congress arbitrarily reduced the Virgin Islands’ eligibility for federal Medicaid dollars by as much as $32 million. For context, federal and local spending on Virgin Islands Medicaid in 2011 was $33 million combined.39

These figures represent a modest estimate when compared to years in which the Virgin Islands Government was limited both by the arbitrarily low reimbursement percentage and the overall funding cap—like in FY2000, when the true funding split was estimated to be just 37% federal and 63% local. Determining the true aggregate cost of decades of unequal treatment under federal Medicaid rules is beyond the scope of this report, but there is little doubt that the amounts in question equal or exceed the Virgin Islands Government’s entire annual budget for low-income health coverage in this scenario.

Viewed from the perspective of the individual enrollee, the numbers are equally striking. In 1998, the average U.S. Medicaid expenditure per recipient was $3,939, with the lowest state average (Georgia) at $2,812.40 In the Virgin Islands, that amount was just $525 per recipient ($275 for children).41 Similarly, the national average expenditure for Medicaid’s Early Periodic Screening and Diagnostic program that year was $76.00 per child, while the Virgin Islands’ average was $1.20.42 These drastic Medicaid funding disparities have compounded over decades, with some years more destabilizing than others. In 1994, the Governor of the Virgin Islands assembled a special task force to “deal with the $372 per recipient received from Medicaid in FY1992, when the true expense locally for care counting all components was $2,799 per recipient.”43

Federal Law's Structural Barriers to Quality Care

The above dollar figures fail to capture the full extent of structural disadvantage that persists within the Virgin Islands’ healthcare system as a result of disparate treatment under federal Medicaid laws and other health policy implementation. In a recent report to Congressional staff, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)—the federal agency responsible for Medicaid—has admitted that it “is aware that the territories often do not cover mandatory services, given the funding cap and limited infrastructure.”44

Looking beyond dollar amounts, one of the most significant practical effects of the Virgin Islands’ reduced federal cost-sharing percentage and arbitrary funding caps is a systemic budgetary uncertainty often referred to as the Virgin Islands’ “Medicaid cliff.” The Medicaid cliff results from an accumulating year-to-year strain on the Territory’s Medicaid system as the local government stretches to fund services with arbitrarily low federal reimbursement rates. Rather than increase the standard baseline of support that the Virgin Islands receives for healthcare access, Congress has instead elected to maintain these comparatively low levels of support as the default and then intervene on an ad hoc basis when it appears that the Territory’s healthcare system is approaching a breaking point.

For example, after decades of deflating the U.S. Virgin Islands’ federal cost-sharing percentages below what the Territory would otherwise receive under the standard formula, Congress temporarily increased the Virgin Islands’ federal reimbursement percentage to 100% in 2018 after the hurricanes destroyed a significant percentage of the islands’ healthcare infrastructure.45 However, Congress enacted this temporary increase for a two-year period only. Despite repeated calls for more lasting solutions, Congress pushed the Virgin Islands to the very edge of the Medicaid cliff in 2019, forcing the Territory to prepare to cut health coverage for 15,000 of its most vulnerable populations—nearly 15% of the pre-hurricane population.46 At the last second, Congress passed a one-month extension, avoiding an immediate crisis while lawmakers considered a new funding package for the territories.47

A few weeks later, Congress passed a second temporary increase, this time rolling back the reimbursement percentage from 100% to 83%, which is the cost-sharing percentage the Virgin Islands would have normally received were it included in the same formula that applies in the 50 states.48 Although the Virgin Islands and other territories advocated for a longer-term increase that would stabilize funding at predictable rates through at least 2025,49 Congress again opted for a two-year solution that will expire in 2021. It is highly uncertain whether the Virgin Islands’ FMAP percentages will be extended past 2021, revert to the pre-Hurricane level of 55%, or land somewhere in between—a range of outcomes that could theoretically double the Territory’s Medicaid budget, or cut it by more than half.50

The Medicaid funding uncertainties leading up to 2019—and now 2021—have constrained the Virgin Islands’ capacity to adapt appropriations toward longer-term needs, such as expanding Medicaid enrollment or remedying provider shortages in the local healthcare economy. Any effort to expand Medicaid and increase income qualification levels under the present system carries the unspoken risk that funding will revert to pre-Hurricane levels during the next budget cycle, leaving the Territory unable to support whatever expanded commitments it makes in the short term. Accordingly, the Virgin Islands’ current Medicaid enrollment rate (17%) lags considerably behind the national average (22%) despite poverty rates exceeding all 50 states.51 The U.S. Virgin Islands’ Medicaid enrollment rate is also the lowest among the five U.S. territories.52

In some instances, Congress’s temporary and ad hoc funding increases do little to improve access to or quality of services. Funding that could otherwise be applied to new initiatives and investments is in many cases absorbed by existing debt obligations or a backlog of unpaid claims. In FY2000, the year when the Virgin Islands’ effective federal reimbursement was just 37% due to the discriminatory funding cap, more than $2.6 million in Virgin Islands Medicaid claims went unpaid, bringing the Territory’s total unpaid claims to nearly $10 million.53 That same year, Congress approved a nearly $1 million increase for the Virgin Islands State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), a funding stream that goes towards the Territory’s Medicaid program.54 However, rather than increase enrollment of uninsured children, the Virgin Islands obtained a waiver that directed the new money towards prior unpaid bills. Similarly, in 2014, the Territory accessed several million dollars in retroactive Medicaid payments that the Virgin Islands Government intended to put towards expanding health insurance and mental health care to those most in need. However, of the $4 million allocated to the Juan F. Luis Hospital on St. Croix, a staggering $1.5 million was immediately diverted to the Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority (WAPA) in order to reduce the facility’s “severely past due accounts.”55

This cycle of systemic underfunding followed by unpredictable, ad hoc interventions keeps the Virgin Islands perpetually at the edge of the Medicaid cliff. Even when Congress steps in to provide additional funds that it withheld in the first place, the abrupt, short-term nature of these policy choices exacerbates many of the broader problems in Virgin Islands healthcare. Without a stable medium- or long-term funding outlook, the Territory has little chance of remedying its acute provider shortages, investing in intermediate- or long-term care options, upgrading its crumbling healthcare infrastructure, or expanding Medicaid coverage to income levels comparable to states. Accordingly, the Territory maintains Medicaid eligibility levels that are significantly more restrictive than low-income states and spends a large percentage of its healthcare budget sending its residents to off-island providers—a system that is both highly cost-inefficient and a frequent cause of individual and family hardships.

U.S. Virgin Islands' Healthcare Desert

The present state of U.S. Virgin Islands healthcare is dire, particularly for low-income and disabled populations. A recent public-private task force on Virgin Islands Hurricane Recovery reported that “[a]pproximately 82 percent of the USVI population is medically underserved and faces a number of health challenges, including limited access to certain specialty services.”56 Meanwhile, the Territory reports higher rates of cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and infant mortality than United States overall.57 To attribute these outcomes to structural issues in federal Medicaid policy (e.g., the Medicaid cliff) requires no creative accounting. Medicaid is arguably the largest driving force within the Virgin Islands’ healthcare economy. Current data indicate that a majority of the Territory’s adult population is either receiving Medicaid or is uninsured (a function of the Virgin Islands’ Medicaid caps and artificially limited federal reimbursements).58

Hurricane impact assessments have identified the flight of on-island health providers—particularly in mental health and other specialty care services—as one of the storms’ most damaging healthcare consequences.59 A public-private task force reported that in the immediate aftermath of the storms, 138 hospital staff voluntarily resigned from the Roy L. Schneider Regional Medical Center on St. Thomas (SRMC) and the Juan F. Luis Hospital on St. Croix (JFL).60 A year after the storms, SRMC reported a loss of 175 nurses.61 Similarly, the Congressional Research Service reports that “many young professionals and healthcare workers have left the USVI” in the wake of the storms, a trend that stands to “complicate recovery efforts in the healthcare sector.”62

However, to attribute the root cause of the present healthcare crisis in the Virgin Islands to the 2017 hurricanes or to COVID-19 would be an error. The present healthcare problems in the Virgin Islands reflect longstanding systemic difficulties exposed and accelerated by external events. The Virgin Islands’ healthcare provider shortages had already reached disastrous levels well before Hurricanes Irma and Maria destroyed both of the Territory’s hospitals and caused more than $10 billion in damage.63

Dependence on Off-Island Services: Draining the V.I. Healthcare Economy

One month before the 2017 storms made landfall, the Virgin Islands’ then-Governor gave an interview in which he detailed some of the dire consequences resulting from the Territory’s uncertain Medicaid status:

[T]ake a pregnant mother who ends up with a premature birth, and that pre[mature] baby needs intensive care. If it’s unavailable on the Virgin Islands, the hospitals have to put that mother and baby on an air ambulance and fly them to the mainland to a facility where they can be cared for. When public hospitals make those decisions, the government of the Virgin Islands foots that bill. We’ve had instances where people have been transferred to mainland facilities, and when it was all finished the bill was over $600,000. That comes directly out of the treasury. 64

Since the 1990s, the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has designated the U.S. Virgin Islands a “Geographic High Needs Health Professional Shortage Area.”65 2019 data from HRSA’s Bureau of Health Workforce indicate that the Virgin Islands remains severely underserved across the healthcare profession even after recent efforts to boost recruitment and retention since the hurricanes. Compared to the rest of the United States per capita, the Virgin Islands currently has less than half the number of licensed practical nurses and psychologists, and only a third as many social workers or nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides.66

The U.S. Virgin Islands’ reliance on air ambulances and off-island healthcare services—especially in Puerto Rico—has increasingly become a norm rather than exception. That some highly specialized medical services may become unavailable in an island territory of roughly 106,000 people is to be expected. For example, the University of Hawaii reported an acute doctor shortage in 2019 that left the island of Maui (population 167,000) without a locally based neurosurgeon or colorectal surgeon.67 In the event of such a shortage, the Territory would predictably send patients off-island for certain specialized medical services or care for certain rare conditions.

But what is occurring in the U.S. Virgin Islands is far more extreme. The U.S. Virgin Islands’ healthcare economy has become so overburdened and underserved that the Territory can no longer provide some of the most basic intermediate- or long-term care services to disabled and elderly citizens or to those with acute mental health needs. To the detriment of the local healthcare economy, the Territory’s Medicaid budgets, patient well-being, and family cohesion, the Virgin Islands must pay staggering amounts to send elderly patients off-island for skilled nursing care, children with developmental disabilities off-island for specialized care, and individuals of all ages off-island for mental healthcare. Beyond draining the Virgin Islands healthcare economy of funds that could drive investment and expand services, removing these patients from family and community settings can have long-term adverse impacts on recovery. The burdens of travel itself can create significant health risks for disabled individuals and their families, with or without a global pandemic.

With respect to elder care, the Virgin Islands is presently without capacity to provide basic nursing home care or long-term care services on-island. Many of these services are covered by Medicaid, but without provider capacity, the Virgin Islands has been forced to ship many of its elders off-island for care. As of 2020, the Virgin Islands has zero Medicare or Medicaid-certified nursing facilities within the Territory. The Territory’s two public nursing homes—Herbert Grigg Home on St. Croix and Queen Louise Home for the Aged on St. Thomas—both have long waiting lists for a vanishingly small number of beds. For the few who do get a spot, these facilities are said to operate in “alarming” conditions.68 The State Director of Virgin Islands AARP recently testified that when he visited the Queen Louise Home for the Aged on St. Thomas, he was “moved to tears and great sadness” because the facility “looked like an abandoned building with people living in it.”69 The only privately run, CMS-certified nursing home in the Virgin Islands, Sea View Nursing Facility, was forced to close in early 2020 after losing its Medicare and Medicaid certifications.70

With an aging population and an increasing number of people in need of long-term care services, the number of patients with unmet needs is growing. Eighteen percent of the U.S. Virgin Islands population is over 65, a proportion that exceeds the U.S. average.71 In early 2020, St. Croix’s only hospital had to send up to ten seniors off-island for nursing care because “the territory has no skilled senior living facilities which can care for the needs of these vulnerable seniors around the clock.”72 This transfer alone cost the Territory $150 per day per individual—a total cost of $4,650 per patient per month.73

Similarly, the Virgin Islands has a chronic and severe need for mental healthcare services.74 The need for mental health services has become so acute that two different Virgin Islands governors have declared a mental health state of emergency since 2016.75 As of April 2019, there were no psychiatric beds available for patients in St. Croix and only a handful in St. Thomas.76 The inpatient psychiatric unit at St. Croix’s only hospital has been closed since 2012, and many of the Territory’s outpatient practitioners left the islands permanently following the hurricanes.77 For some with severe mental illness, there is often nowhere to go but jail—and none of the Territory’s jails has a forensic unit to house or care for mentally ill inmates.78

This comes at the same time that the risk of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and other mental health conditions has spiked in the aftermath of the hurricanes. One study suggests that more than half of Virgin Islands adults—57%—are at risk of PTSD and in need of mental health support.79 One Virgin Islands doctor has explained that the Territory is experiencing “an epidemic of people who have gone through significant psychological trauma . . . [t]he storm did not spare any demographic. The psychological scars will remain for a long time and need to be addressed acutely and chronically.”80

Even before the hurricanes, the Virgin Islands Government was paying “millions of dollars a year to house [mental health] patients off-island,” including adolescents.81 As of 2019, the Virgin Islands was paying for 26 residential mental health clients to be housed off-island, at a cost of $6.5 million to $7 million per year ($270,000 per year per patient). According to the St. Thomas Source, the total for off-island care is closer to $20 million annually, a figure that includes children and adolescents sent off-island for mental health care by the Virgin Islands Department of Human Services.82

There are still more off-island mental health care expenses resulting from the Virgin Islands’ dearth of on-island services. Perhaps most concerning are the costs associated with the Virgin Islands Bureau of Corrections (BOC) in meeting the mental healthcare needs of the Territory’s inmate population, many of whom wind up incarcerated because of the lack of alternative mental health interventions. According to the current Virgin Islands BOC director:

Virgin Islands residents suffering from acute mental illness are brought to [BOC] facilities by default because there is nowhere else to put them. That means that an inmate with mental illness, who may not have committed any crime, may spend months or even years at the St. Thomas Jail pending appropriate treatment. One inmate, LC, who suffers from chronic schizophrenia, has been incarcerated for over 8 years while awaiting trial.83

Not only does the lack of mental health services mean that persons with mental illness are far more likely to be avoidably incarcerated; it creates significant secondary costs for the Virgin Islands BOC, which sends a significant portion of its inmates off-island because the Territory lacks resources and capacity to house these inmates within Virgin Islands facilities, especially when it comes to inmates requiring mental health care. According to 2019 estimates, the Virgin Islands has been spending $12 to $15 million per year to house between 179 and 194 inmates at outsourced off-island facilities.84 In 2019, the Virgin Islands contracted to pay $2.4 million annually to house just fourteen chronically mentally ill inmates at a stateside facility ($172,000 per mentally ill inmate per year).85 On top of these costs, the BOC director recently testified that the agency “has been exploring the possibility of transferring seriously mentally ill prisoners to an off-island facility in South Carolina,” adding that the “cost of housing these mentally ill prisoners off-island will be substantial” over and above what the Territory already spends to house its own prisoners elsewhere.86 Finally, as a result of a shortage of outpatient services in the Territory, it is exceedingly difficult to successfully reintegrate formerly incarcerated persons or discharge patients with acute psychiatric episodes to a continuum of care in the community.87

Many of these unmet residential care and other long-term care needs would be greatly alleviated by making home or community-based care alternatives available within the Territory under Medicaid. All 50 states currently operate some form of Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Medicaid waiver program, which permits persons with disabilities, adults and children with developmental disabilities, elderly persons, and others to have in-home medical and non-medical services covered by Medicaid (including, for example, homemaker, home health aide, and personal care services). These HCBS waivers are currently unavailable in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

HCBS waivers are especially important for individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities (IDD) as an alternative to residential care in an intermediate care facility (ICF). HCBS waivers allow persons with IDD to remain in their home community, affording them greater autonomy and quality-of-life benefits while reducing the overall cost to Medicaid programs. The costs of providing care within the home or an assisted living facility are estimated to be a fraction of costs associated with nursing homes or ICF care.88 The Virgin Islands is not statutorily barred from establishing an HCBS waiver program, but doing so would require some degree of administrative overhaul and sustained investment, including amendments to the Virgin Islands’ Medicaid state plan, investment in new provider relationships, and the creation of new administrative and oversight systems.89 A more permanent, stable Medicaid funding structure would enable the creation of an HCBS waiver program for the Virgin Islands

As with other problems facing the Virgin Islands’ healthcare ecosystem, the problem of over-dependence on off-island services accelerated rapidly in the immediate aftermath of the 2017 hurricanes, when the Virgin Islands’ two hospitals were forced to transition nearly one thousand patients to the U.S. mainland.90 Nearly a year after the storms, some patients were still unable to return because a number of critical outpatient services (including dialysis and cancer treatments) remained unavailable at that time.91

Two years after the storms, one of the Territory’s hospital directors told the Virgin Islands Legislature that there continued to be “a heavy reliance on off-island transfers to hospitals in Puerto Rico and on the mainland due to the loss of inpatient bed capacity and a lack [of] specialty services.”92 “On average . . . there is [one] patient transferred off island per day, every day. This results in millions of healthcare dollars leaving the island of St. Croix and the separation of families when they are most vulnerable and in need of family support.”93 Additionally, as the availability of quality healthcare services continues to decline, wealthier patients with private insurance or air ambulance coverage increasingly seek care off-island, channeling further revenue away from Virgin Islands hospitals and providers. Together, these forces risk launching the Territory’s healthcare economy into a downward spiral.

With more predictable and stable support from Medicaid, the Virgin Islands could undertake more substantial initiatives to attract new providers and develop new facilities. Instead, the Virgin Islands is forced to brace itself for yet another Medicaid cliff approaching in 2021. Policymakers must pursue structural solutions that will remove the Virgin Islands from its perpetual limbo status and close the widening gap in health access between the U.S. territories and mainland communities with comparable poverty rates. If the federal reimbursement percentage reverts back to its pre-hurricane rate of 55% in 2021, the Virgin Islands stands to lose nearly half of its program spending, which could cause a majority of the Territory’s low-income enrollees to lose their health coverage.94

Unequal Treatment Under Federal Supplimental Security Income (SSI)

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Overview

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is the largest federal cash assistance program in the United States. SSI provides monthly income assistance to people who (1) are disabled, blind, or elderly, and (2) have minimal or no income and few assets. SSI is an essential lifeline for the nation’s most vulnerable populations—except for those living in the U.S. Virgin Islands and other U.S. territories excluded from the program.

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) is the largest federal cash assistance program in the United States. SSI provides monthly income assistance to people who (1) are disabled, blind, or elderly, and (2) have minimal or no income and few assets. SSI is an essential lifeline for the nation’s most vulnerable populations—except for those living in the U.S. Virgin Islands and other U.S. territories excluded from the program.

Unlike Social Security retirement benefits or other social insurance programs, SSI does not require beneficiaries to have “paid in” before receiving benefits. It is a fully-funded federal program that does not consider an individual’s past taxpayer contributions.

In September 2020, more than eight million Americans received SSI, including more than one million disabled children.95 For the majority of these recipients, SSI was their only source of income. It is also the only federal income support program targeted at families caring for children with disabilities96

For 2021, a qualifying disabled, blind, or elderly individual can receive up to $794 per month in cash assistance under SSI.97 A qualifying couple can receive up to $1,191 monthly. SSI is in every sense a program of last resort: individuals with more than $2,000 in combined assets cannot receive benefits, and nearly half of adult SSI recipients still live beneath the federal poverty level while receiving benefits.98

According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, “SSI benefits lift half of otherwise-poor child beneficiaries out of poverty. Benefits particularly reduce deep poverty, lifting nearly 200,000 children with disabilities above 50 percent of the poverty line . . . .”99 The combination of federal medical support (through Medicaid) and income support (through SSI) is the foundation of low-income disabled Americans’ well-being. With zero access to SSI and diminished access to Medicaid, the Virgin Islands’ disabled, blind, and elderly populations face multiple dimensions of disadvantage and discrimination compared to the rest of the country.

Discriminatory SSI Exclusion for U.S.Virgin Islands

Congress has enacted special legal provisions within SSI that make residents of the U.S. Virgin Islands completely ineligible for benefits. In lieu of SSI, Congress has maintained separate, lesser programs for people living in the Virgin Islands and other territories. These programs, commonly referred to as “adult assistance programs,” are a patchwork of federal block grants that provide a tiny fraction of the support that would otherwise be available under SSI. They include: Old Age Assistance (OAA), Aid to the Blind (AB), Aid to the Permanently or Totally Disabled (APTD) and Aid to the Aged, Blind, and Disabled (AABD). The U.S. Virgin Islands receives federal support through the first three programs (OAA, AB, and APTD), while Puerto Rico receives its federal support through one combined funding stream (AABD).

Unlike SSI, none of the territories’ alternative disability assistance programs under OAA, APTD or AABD offers benefits to disabled children.100

Although the average SSI recipient in the U.S. mainland receives nearly $600 per month in cash assistance (and in some cases nearly $800 per month), the average benefit in Puerto Rico—one of the territories excluded from SSI—was just $77 per month in 2019 (only $58 of which came from the federal government).101 In 2011, the average payment to benefit recipients in the Virgin Islands under OAA, AB, and APTD combined was $176.07 per month.102 The funding gap is made worse by the fact that federal adult assistance in the territories requires the local government to fund 25% of all benefits, whereas the federal government covers 100% of all benefits under SSI.

As with Medicaid, these separate, lesser adult assistance programs are also subject to a discriminatory ceiling that caps federal support at a specified maximum.103 For the Virgin Islands, Congress has set a restrictive funding cap that applies not only to the aforementioned adult assistance programs like OAA, AB, or AABD, but also to the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program and other programs supporting adoption assistance, foster care, and independent living. The “mandatory ceiling amount” for the U.S. Virgin Islands’ federal cash assistance programs is fixed at $3,554,000—a cap that is not indexed for inflation and has not changed since 1997.104 However, with nearly $2.9 million of that cap taken up by the Virgin Islands’ TANF block grant, the total remaining amount available for income support to the aged, blind, and disabled—as well as foster care, adoption assistance, and independent living—is only about $700,000 total.105 Accordingly, only about 1,000 Virgin Islanders received any kind of benefit under OAA, AB, or APTD in 2011.106

The Government Accountability Office has suggested that if Congress were to grant full access to SSI in U.S. territories, nearly ten times as many disabled, blind, and elderly persons could receive benefits under these programs. In Puerto Rico alone, a transition from AABD to SSI would have raised enrollment from 37,500 to an estimated 354,000 persons in 2011.107 For Puerto Rico in 2011, the gap between the federal dollars the Territory would have received if eligible for SSI ($1.8 billion), and the actual federal funding it received through AABD ($26 million), represents a difference of 70x in just one year.108

Unlike Medicaid, which excludes all U.S. territories from the standard cost-sharing formula, SSI excludes only some of the territories from benefits. Congress has determined that residents of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands are fully eligible for SSI benefits, while residents of the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and American Samoa are not. Residents of Washington D.C. are also fully eligible for SSI benefits.

In some cases, Virgin Islanders can receive SSI support if they leave the Virgin Islands and establish physical presence in one of the 50 states, Washington D.C., or the Northern Mariana Islands. However, these Virgin Islanders would lose all benefits if they were to return home for thirty (30) or more consecutive days. To become eligible again, that person would have to return to the states, Washington D.C., or the Northern Mariana Islands and reestablish a physical presence for another thirty (30) consecutive days.

As a result, there are many Virgin Islanders—including a large number who were displaced after Hurricanes Irma and Maria—who cannot afford to remain in the Territory or return home for fear of losing access to their lifeline of last resort. This discriminatory exclusion has devastating consequences for many families with disabled, blind, or elderly family members, and is increasingly subject to constitutional scrutiny. Federal courts have recently held that Congress’s decision to exclude U.S. citizens living in Puerto Rico and Guam from SSI benefits is unconstitutional. SSI’s blanket denial of benefits to the U.S. Virgin Islands has yet to be specifically challenged in either the local or federal courts in the Virgin Islands, and one of the successful constitutional challenges from Puerto Rico is currently pending before the United States Supreme Court.109 Regardless of how the courts intervene with respect to federal discrimination in SSI benefits, local and federal policymakers should act with urgency to remedy ongoing harms to one of the nation’s most underserved and unrepresented populations.

Real-World Impacts: Unequal Treatment Under SSI

Being excluded from the nation’s largest federal cash assistance program has significant consequences for Virgin Islanders, both within the Territory and across its diaspora. Whereas SSI benefits lift a significant percentage of the nation’s low-income disabled persons out of extreme poverty in the fifty states, Washington D.C. and the Northern Mariana Islands, the federal government tolerates unconscionable outcomes among elderly and disabled populations of the Virgin Islands, where cost-of-living is among the highest in the United States.110

The populations most severely impacted by Congress’s decision to continue excluding the Virgin Islands from SSI are low-income disabled children and their families. Families at or near the federal poverty level are significantly more likely to experience food insecurity and other extreme economic hardship when they have one or more disabled children.111 Even when a disabled child lives with one or more working parents, those parents’ additional expenses and time-demands often lead to significant losses in household income. According to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, nearly 40% of children receiving SSI require extra help with daily life activities, including “mobility, using the toilet, eating, bathing and dressing.”112 Accordingly, “[p]arents, as primary caregivers, often must provide this kind of care,” since “[f]ew child care providers will serve children with intensive daily needs, forcing many parents to cut back on work or leave the workforce altogether.”113

Research indicates that families caring for disabled children are “twice as likely as families with nondisabled children and with the same level of income to face material hardships such as food insecurity (for example, skipping meals or running out of food) and housing and utility hardships (for example, being unable to pay rent or having utilities shut off).”114 These risks are especially high in the Virgin Islands, where food, housing, and utility costs are all significantly above the U.S. average. The last of those risks is particularly salient, as U.S. Virgin Islands electricity costs are among the highest in the world—300-400% above the national average.115

Exclusion from SSI benefits, coupled with diminished access to Medicaid, generates hardships that will impact children with disabilities into adulthood. There is a substantial body of research concerning the effect of poverty on child development showing that long-term safety net programs dramatically improve school performance and translate to higher earnings as adults.116 By the same token, research shows that “[g]rowing up poor and with a disability poses further challenges for children receiving SSI. Childhood health problems — especially mental health problems — damage adult prospects.”117 As detailed in earlier sections of this report, federal income support through SSI lifts a significant percentage of the country’s disabled children out of poverty conditions. Accordingly, the decision to exclude disabled Virgin Islands children from this program jeopardizes their chances of successfully transitioning into adulthood, entering the workforce, and generally living healthy and independent lives.

There are additional collateral impacts of the Virgin Islands’ SSI exclusion. For example, there are other federal benefits, programs, or incentives that link eligibility to SSI benefits. In employment, the federal Work Opportunity Tax Credit (WOTC) incentivizes private employers to hire persons from groups that are historically disadvantaged in private employment, including disabled or formerly incarcerated individuals. One major barrier to accessing this tax credit in the Virgin Islands is that one of its primary eligibility categories is linked to SSI benefits. There are many disabled persons in the Virgin Islands who, if eligible for SSI, would be attractive candidates for employers seeking to take advantage of the WOTC. There are currently about 100 Virgin Islands employers who claim this federal credit every year, mostly in connection with hiring non-disabled persons receiving SNAP benefits.118 If Virgin Islands employers were able to hire candidates who have received SSI within the last sixty days, they could claim 40% of wages paid up to $6,000 as a credit per employee.

There are still more negative impacts stemming from the Territory’s SSI exclusion. Vocational rehabilitation programs—another essential resource for ensuring the well-being and independence of disabled persons—are also linked to SSI benefits under federal law. Under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, individuals who receive SSI are considered automatically eligible for federally funded vocational rehabilitation unless they are too significantly disabled to benefit from the program. Paradoxically, the Virgin Islands Department of Disabilities and Rehabilitation Services’ public outreach materials specify that “[i]ndividuals who receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) . . . are considered eligible” for the Territory’s vocational rehabilitation programs, even though by law no resident of the Virgin Islands can receive SSI.119

In a recent court filing challenging the constitutionality of federal discrimination against residents of U.S. territories for SSI benefits, Puerto Rico’s nonvoting member of Congress argued that of all the disparities facing Americans living in U.S. territories, “none is as shocking to the conscience as the disparity in the assistance available to the most vulnerable citizens, people who under no circumstances can support themselves.”120

Growing Constitutional Concerns

SSI’s discriminatory exclusion of U.S. territories has recently been declared unconstitutional by four different federal courts.121 One of these decisions is currently pending review by the United States Supreme Court.122

In each of these cases, the United States government has unsuccessfully argued that this discrimination is justified by some combination of the following three reasons: (1) that U.S. territories’ income taxes generally do not go to the federal treasury; (2) that extending federal benefits to the territories would be expensive for the federal government; and (3) that increasing current benefit amounts may disincentivize individuals from entering the workforce or otherwise cause economic disruption.

In this recent wave of litigation, federal judges have strongly dismissed each of the above arguments and instead held that the discriminatory SSI exclusion violates the U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws. In response to the federal government’s argument that territories can be excluded from SSI benefits because their residents’ income taxes do not go to the federal treasury, a federal appeals court held that “the idea that one needs to earn their eligibility by the payment of federal income tax is antithetical to the entire premise of the program[,]” since “any individual eligible for SSI benefits almost by definition earns too little to be paying federal income taxes.”123

In response to the federal government’s next argument, that benefits need not be extended to the territories because Congress determined that doing so would be costly to the federal treasury, another court held that cost alone is “never a valid reason for disparate treatment,” adding that the rationality of the exclusion is undermined by the fact that Congress has already granted SSI benefits to one U.S. territory: the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.124

The United States’ third argument in these cases, that Congress rightfully excluded the territories from benefits like SSI because granting them would cause economic disruption or disincentivize work, has attracted even greater scrutiny from courts. In response to this proposed justification, a unanimous panel of federal appellate judges responded that “[a]ny concerns related to ‘economic disruption’ should be met with suspicion,” while another judge noted that “[s]evere poverty and the problem of work disincentives apparently posed no obstacle to providing full [benefits] on American Indian reservations.”125

The scope of these recent constitutional challenges has been primarily limited to SSI benefits in Puerto Rico and Guam, although one of these cases goes further and challenges Puerto Rico’s exclusion from food stamps (SNAP) and Medicare Part D Low Income Subsidies (LIS) in addition to SSI.126

The Costs of Federal Disenfranchisement

That federal law maintains separate rules for U.S. territories in certain federal programs is not itself a problem in all circumstances. In many instances, U.S. territories have sought to enact special protections under federal law to preserve culture, environment, or other key interests while these communities work towards self-determining the future of their relationship with the United States. Similarly, there are special Medicaid rules that increase the federal cost-sharing percentages for tribal reservations and for Washington D.C.—providing historically excluded or disenfranchised communities with more generous assistance than they would receive under the standard formula.127

In the overwhelming majority of instances, however, these separate rules are created without meaningful input from the people of the territories and are not designed to serve the interests of their future self-sufficiency or self-determination. Within the context of federal benefits, these separate and unequal rules almost always serve to reduce the federal government’s economic commitments to developing and supporting low-income communities of color. This is politically possible in large measure as a result of the territories’ lack of voting representation in Congress and for the Presidency.

Much has been written about the costs of disenfranchisement and political invisibility for Americans living in U.S. territories. The territories’ lack of representation across all three branches of the federal government goes directly to the heart of the most pressing problems facing these communities today. With respect to the voicelessness of U.S. citizens in the territories, the Virgin Islands’ Delegate to Congress recently wrote that “disenfranchisement of four million citizens, quite literally marginalized at the fringes of our national map, remains a troubling blind spot in today’s conversation around racial justice.”128 Noting that Virgin Islanders in the military continue to serve under a commander-in-chief for whom they cannot vote, she argues that “for the last one hundred years, our sons and daughters have borne every responsibility of U.S. citizenship while being denied many of its most fundamental promises.”129

Drastic action will be needed to fully enfranchise the U.S. Virgin Islands and other territories after more than a century without a seat at the table. Currently, the Virgin Islands has zero electoral votes for President, zero Senators, and one Delegate to the House of Representatives who is not allowed to vote on the floor. Still, with respect to Medicaid, SSI, and other issues of federal lawmaking, the Virgin Islands’ representation in the House—even if it is technically nonvoting—has played an important role.

In fact, the House of Representatives has passed numerous bills that would have lifted or eased many of the federal benefits restrictions that currently harm the territories’ most vulnerable populations. Going back to 1972, there is a long history of House action that has been either ignored or reversed by the Senate, where the Virgin Islands has no formal voice at all.

In 1972, 1975, 1976, and 1977, the U.S. House of Representatives passed amendments that would have extended SSI benefits to U.S. territories. Each time, however, the U.S. Senate either removed or failed to act upon those amendments.130 There have been many more unsuccessful bills in the House introduced by the nonvoting delegates from the territories, who have been able to push the issue onto legislative agendas even if they lack the voting power to actually change these laws. Even during passage of the Affordable Care Act, Virgin Islands officials noted that “the House version was much more generous to the Territories originally, but ultimately the Senate version, with considerably less funding for the Territories, was passed.”131

As an interim step to obtaining full enfranchisement for the Virgin Islands, the Territory should seek increased representation before the U.S. Senate and its committees to ensure, at the very minimum, that the perspectives and needs of the U.S. Virgin Islands are not lost or ignored as bills move through the legislative process from the House to the Senate.

In the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, voting is the right “preservative of all rights” under the American system of government.132 On some level, the dire state of Virgin Islands healthcare and lack of support for disabled children and their families can both be traced to the blanket disenfranchisement of Virgin Islanders in Washington D.C. Any structural, systemic solution must acknowledge the relationship between these disadvantageous legislative outcomes and the Territory’s absence from the table at which they are decided.

Inadequate Federal Data Collection and Reporting for U.S. Territories

One difficulty in attempting to accurately measure economic or health impacts of federal benefits discrimination on the Virgin Islands’ disability community is the lack of uniform federal data collection and reporting with respect to U.S. territories. Not only do federal agencies fail to include relevant data for U.S. territories in important places where national figures are broken down by state, there are also instances where the federal government reports data inconsistently even among the five territories (for example, by reporting certain statistics for Puerto Rico but not for the U.S. Virgin Islands).

In the course of compiling this report, DRCVI encountered numerous gaps in key data that are readily available for the rest of the United States. For example, the IRS Data Book, a staple of policymaking at the state, local, and federal levels, provides much-needed visibility on the various forms of federal tax collections across the fifty states, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. It does not, however, provide equivalent visibility for advocates and policymakers in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Throughout the IRS’s Data Book, data specific to federal collections in the U.S. Virgin Islands is lumped together with other territories’ federal collections in overbroad categories such as “Other”133 or “U.S. Armed Services members overseas and Territories other than Puerto Rico.”134

More significantly, the federal government does not collect or report U.S. Virgin Islands’ demographic, disability, labor participation, income, housing, migration and other data to the same extent or frequency as in the fifty states, Washington D.C., or Puerto Rico. In addition to running the decennial census, the U.S. Census Bureau collects important data through its American Community Survey (ACS), an annual demographics survey that is the backbone of considerable academic research and government policymaking across the country. The Virgin Islands—along with Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and American Samoa—are not included in ACS. As a result, policymakers often must wait until the next decennial U.S. Census to obtain access to critical data that informs economic outlook and policymaking.

The Virgin Islands’ exclusion from ACS and other national demographic data has an adverse impact on the Territory’s ability to secure grants and advocate for greater federal assistance to meet its needs. According to one of the Virgin Islands’ most prominent demographic researchers, Census Bureau data is the “principal method the U.S. Government uses to distribute a wide variety of assistance to States and local governments.”135 Accordingly, “by applying a whole different approach to us alone, [the Virgin Islands] are deprived access to all kinds of Federal assistance,” including “Medicaid, programs to assist children and families such as child poverty, and support programs for [education]. With annual data, we would be able to assess local needs such as where new roads, schools, and senior citizen centers should be located.”136

One of Guam’s former delegates to Congress argues that the U.S. Census Bureau’s inattention to data collection and reporting for U.S. territories “makes sound public policy decision-making very difficult . . . result[ing] in disparities in treatment of Americans residing in the territories, as compared with Americans residing in the 50 States under certain Federal programs.”137